Welcome to the great outdoors, the best place to study natural history

Indoor laboratories equipped with technology are essential to scientific research. But when it comes to natural history — the study and observation of animals and plants in their habitats — nothing beats being outdoors. From a saltwater cove in Jamestown, to a freshwater pond in Warren, to flowering rain gardens on Providence College’s 105-acre campus, students are engaging in authentic field research, guided by professors who understand the importance of learning beyond the lab and lecture hall.

By Vicki-Ann Downing

Each September finds the Marine Biology students of Dr. Jack Costello, professor of biology, at Fort Wetherill, a protected saltwater cove on the island of Jamestown, 35 miles from Providence. The students measure the variables that describe all marine communities — plankton and benthos, water temperature and salinity — but it’s more than a day at the beach.

“For three or four weeks, they get to be physically in the water and see some of the communities we study — seagrass, rocky intertidal and planktonic communities,” said Costello. “The overall goal is to experience the field, learn the primary methods used to describe marine communities, and then communicate that knowledge in both written and oral form.”

When their field work is complete, the students spend the rest of the semester analyzing the data, writing the results in science manuscript format, making oral presentations on a component of the field work, and more deeply researching an organism that interests them.

Shalan McDonagh ’18 (Cranford, N.J.), who majored in both biology and global studies, called the course “a great balance between lectures and outside lab experience.”

“We were able to see firsthand what we were learning about in our lectures and textbooks,” said McDonagh. “We learned field techniques that can’t be learned from inside the classroom or through a book. We were exposed to a different side of marine biology. There’s the memorization part and studying the species, and then there’s the actual data collection component and observations that are made in the field.

“We were shown the realities of working in the field — that there will be days when you still have to go in the water even if it’s raining and the air temperature is 50 degrees, or when the waves are so strong that you hope you stay in the boat while trying to collect and record data.”

McDonagh will continue her work next year as a technician in a water quality research laboratory at the University of Massachusetts, Dartmouth.

There are no laboratory walls, either, for students who study Wildlife Biology and Conservation with Dr. Jonathan L. Richardson, assistant professor of biology. In a freshwater pond in Warren, Richardson’s students sample aquatic organisms and water quality, and they trap and release small mammals to estimate the number of species, their abundance, and how they’re distributed in habitats.

“Every week we are outside in the field getting our hands dirty,” said Richardson. “I am a firm believer that you can’t learn much just by reading a textbook and listening in a classroom.”

“I wanted a lab that wasn’t a standard lab. I wanted to do something different,” said Richardson. “I’ve had a handful of students that spend a lot of time outdoors and love that component, but for the majority, there definitely was some getting comfortable with the idea of doing something outside. I was convinced at least two students had never been on a hiking trail before.

“That is part of what I find important. It’s the last chance I’ll have to expose them to things they’ll never be exposed to again. Even if they’re initially uncomfortable in a foreign environment, it’s a huge win.”

Rhode Island’s location on the coast, with multiple waterways, makes it easy for students in Richardson’s Freshwater Biology course to venture out in boats on Georgiaville Pond in Smithfield and the West River in Providence to sample water chemistry and animal communities. They study alewife populations on the Monument River near Cape Cod and visit a fish hatchery in Connecticut. Students in Costello’s Invertebrate Biology course collect specimens from Narragansett Bay and from local streams.

Other professors use the outdoors, too. Dr. Patrick J. Ewanchuk, associate professor of biology, teaches an Ecology course in which students learn about New England habitats firsthand by experiencing rocky coastline, salt marshes, forests, and bogs. Dr. Elisabeth Arévalo, associate professor of biology, brings Animal Behavior students to nature conservation areas, an apiary, and a rescue center for parrots and exotic birds. On campus, students observe squirrels and birds.

Dr. Maia F. Bailey, associate professor of biology, and Lynn M. Curtis, assistant professor of art, co-teach a new course, Field Botany: Observing Nature. Bailey, who joined the faculty in 2007, was a biology major and fine arts minor in college. Curtis, who has taught at PC since 1998, is an avid gardener and the daughter of a microbiologist and a bacteriologist, and often teaches biology majors in her art classes.

Their students use the outdoor science classroom, adjacent to the Science Complex, to observe and draw plants growing in a bioswale, or rain garden. Curtis miniaturized an artist’s kit for each of them, complete with a field notebook, pencils, pens, watercolors, brushes, and erasers. Bailey sketches alongside them.

“More and more students do not have a personal relationship with nature, which makes it hard to teach biology,” Bailey said. “Students may have personal relationships with pets, or have a parent who gardens, but are unfamiliar with nature. If we want students to be conservationists, if we want them to be less anxious, if we want them to be good scientists, they need that relationship, and that personal, aesthetic experience.”

James Sullivan ’19 (Holbrook, Mass.), a biology major on the pre-med track, said the course gave him the opportunity to do research in an outdoor lab while also learning about drawing. He enjoyed Bailey’s teaching style so much that he now works as a student researcher in her lab, studying the genetics of plants.

“The course was relaxing, but it had a challenging work component,” said Sullivan. “Sometimes we would draw and other times we would go out to the bioswale to observe. We also worked on our individual projects on our own time.”

For Sandra-Kelly Atkinson ’18 (New York, N.Y.), a biology major and art history minor, the course was a natural fit. Her Drawing I course, taught by Curtis, also went outdoors. But observing in the bioswale presented some challenges.

“The first time we went out, the plants were really tall and overwhelming, bees were flying everywhere, and we appreciated the shade we got from the trees,” said Atkinson. “We drew exactly what we saw — petals, color, and orientation.”

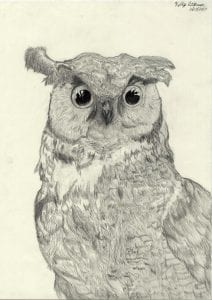

The class took field trips to the Nature Lab at the Rhode Island School of Design and to the Botanical Center at Roger Williams Park, both in Providence. For her final project, Atkinson made a graphite pencil drawing of a great horned owl she saw at RISD.

At first, the professors had to discourage the students from photographing the plants with their phones, then sketching them from photos on the screen.

“Even though we have photography, and photography does some things really well, drawing is a process that involves more than your eyes,” said Curtis. “Observations register differently when you draw. You have a physical, three-dimensional understanding of the subject.”

Curtis showed students Charles Darwin’s field sketches as examples.

“I love working with science professors who study real physical things in the world, particularly the visible, natural world,” said Curtis.

“Drawing is a mindfulness activity, a slowing down, observing, getting your own personal feel for the organism,” Bailey said. “Students don’t get a lot of that.”

“We hope to whet their curiosity and appetite for asking questions about the world,” said Bailey. “We need to reclaim natural history as part of our formal teaching.”