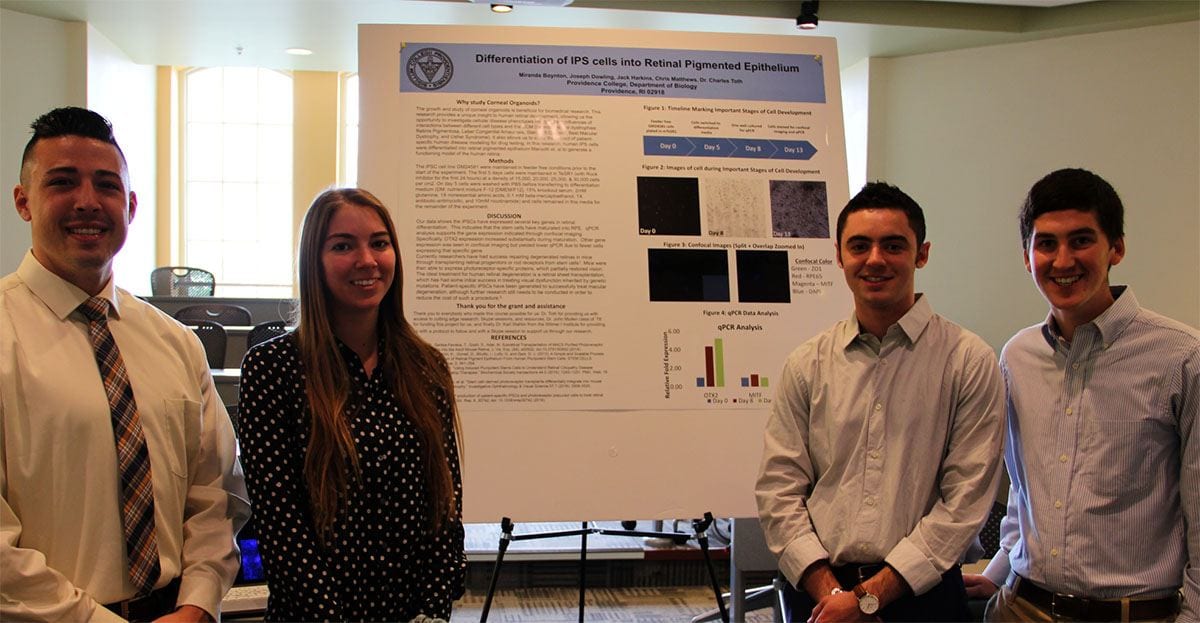

Biology students’ stem cell research takes off

By Chris Machado

Whether it’s cataracts, kidney stones, or cancer, advances in treating these diseases and disorders have begun under a microscope at the cellular level. If you think the road to discovery requires a Ph.D., a group of Providence College biology students recently proved otherwise.

This past semester, Dr. Charles Toth, associate professor of biology, led a first-time seminar entitled Human Organoids. The aim of the lab-intensive course was to grow cellular versions of human organs, such as a kidney, pancreas, and a retina.

“When Dr. Toth introduced us to this, I was excited because we were going to be working on something that is happening in research right now,” said Joseph Dowling ’18 (Ronkonkoma, N.Y.), a biology major who worked in a retina group.

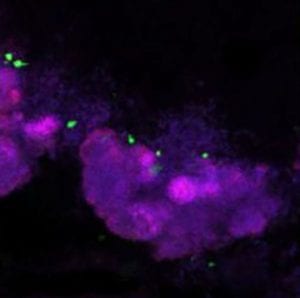

The teams of students created organoids — artificially cultivated masses of cells or tissue that resemble an organ — using human-induced pluripotent stem cells, which were made possible through a gift by John Mullen M.D. ’78.

“Stem cell research is so incredibly important, as this might be the true pathway — along with immunotherapy — to cure so many conditions that plague humanity,” said Mullen, an orthopedic physician. “It can’t be stressed how important this is.”

The stem cells used in the PC lab, which are adult human cells that have been reprogrammed as stem cells, were subjected to various tests that were intended to see if the organoids could mimic natural human behavior. In each group, that happened.

In offering the course, Toth said he wanted to create an open-ended, project-based learning exercise that put the students in control. He charged the students with determining which organoid to grow and which research protocols to follow and scientists to contact, as well as performing the cell cultures and analyses.

“I was extremely proud of the students for stepping up to the plate and owning their work,” he said. “I attended an international stem cell conference recently and met up with a kidney organoid scientist that the kidney group was working with. He saw their completed poster and commented that he was surprised it worked. But, he was very impressed with how well the students did on their project.”

While Dowling admitted that there were disappointments throughout the semester, after weeks of tests he said the outcomes were staggering. The group’s data showed that several of the organoids matured into a tissue known as RPE (retinal pigment epithelium), which has several functions, including light absorption.

“Our main goal was to see if what is being done by researchers was replicable in a classroom environment,” Dowling explained. “We were holding our breath trying to keep these organoids alive. When we got the last (cell) line to work, it was super rewarding.”

Dowling explained that much of this type of organoid research is used for drug screening and testing. But, he added that current research around the country has seen teams create something of a body on a dish — cellular representations of every human organ on a lab dish. Combining those aims of drug testing with the ability to create functioning organoids is an advance that he calls a “triple win.”

“It is incredible,” Dowling said. “This could save pharmaceutical companies millions, it’s safer, and drugs would be cheaper.”

Aside from the benefits in the pharmaceutical world, Toth underscored that the actual lab experience provided the real value to the students — noting how important lab involvement is when students apply to graduate school or post-college jobs.

“I searched and was unable to find a course like this being offered in the U.S.,” he explained. “There are lecture-based courses and mini-courses from companies that offer classes on organoids but nothing specifically to train undergraduates on the science.”

Mullen agreed, saying, “Hands-on research prepares science students for what will be forthcoming in their pursuits in science. If they see and do research early they will be so much more comfortable when they get to the next level.”